November 2024

The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) released a report last year that examined “Concentration and Competition in U.S. Agribusiness.” The three authors—James M. MacDonald, Xiao Dong and Keith O. Fuglie—are economists, and they were able to analyze data that was not publicly accessible to researchers outside of their organization. They focused on three sectors: seeds, meat processing, and grocery retailing.

I have also studied concentration and competition in these sectors, but my background is in a different discipline, sociology. I am not in agreement with one of their main conclusions—that “high concentration can often result from innovations or the realization of scale economies that improve productivity and reduce costs and prices.”

In this post, I visualize some of their data for the seed industry, and critique the emphasis on this rationalization for the increasing power of dominant agribusiness firms.

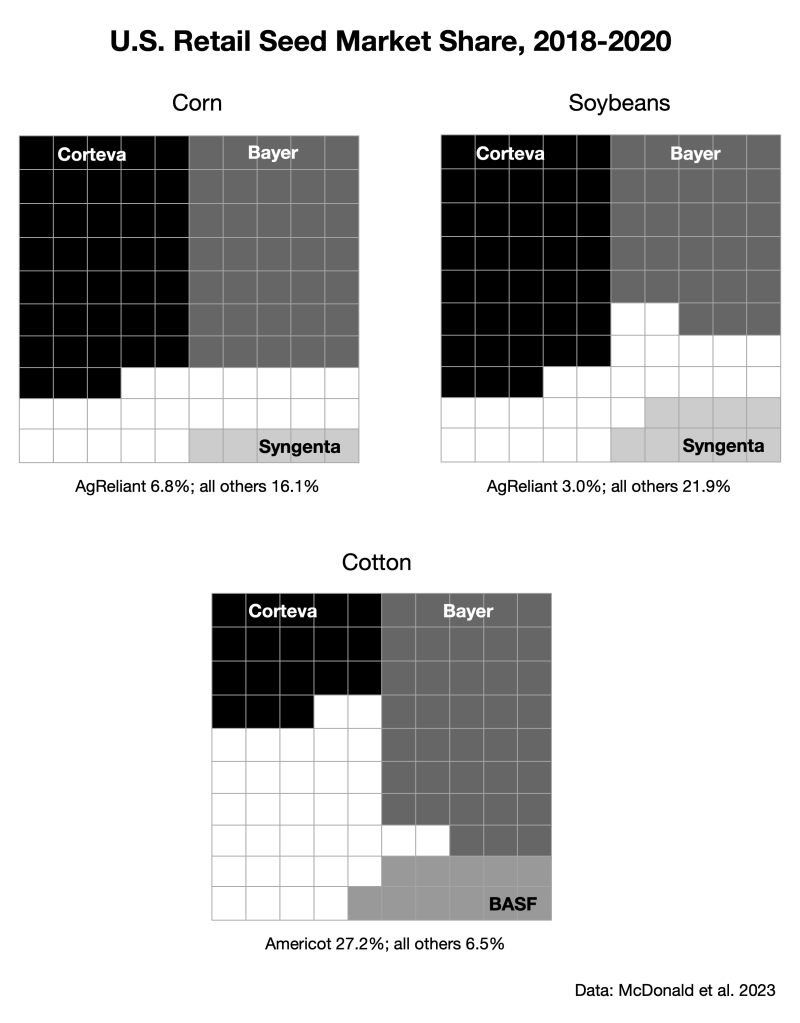

The figure below shows the U.S. retail market share for three major seed markets: corn, soybeans and cotton. Just two firms, Bayer and Corteva, account for 71.6% of sales of corn, 65.9% of soybeans, and 55.9% of cotton.

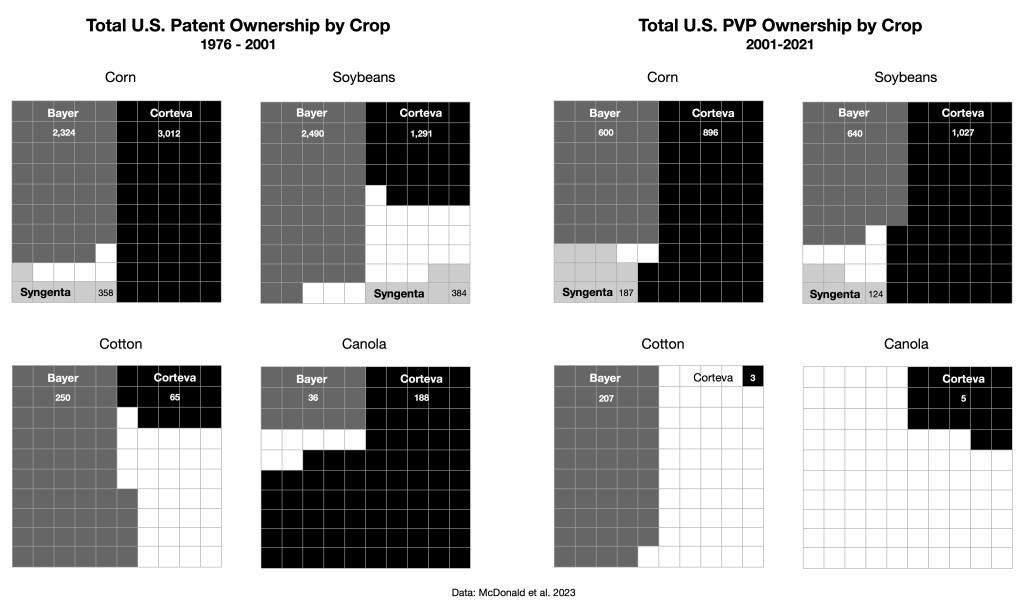

The next figure shows intellectual property protections held by Bayer, Corteva and Syngenta for these crops. Note that for corn, approximately 95% or more of intellectual property protections are held by these three firms.

MacDonald et al. note that increasing concentration in these markets coincided with rapid price increases, such as a 270% rise between 1990 and 2020, compared to commodity price inflation of 56% during this period. They assert, however, that this increase is a result of the value of seed innovations, such as higher yields and lower farm production costs. The authors do not mention that such gains are largely from a reduction of crop losses, rather than intrinsic increases in yield (IAASTD 2008). They also do not point out that these advantages are being eroded by increasing resistance to Bt toxins in insects (Gassmann & Reisig 2023) and increasing glyphosate resistance in many weeds (Bain et al. 2017). Their discussion highlights the research investment that dominant firms are making, which they suggest has remained constant as a percentage of sales—therefore higher seed prices are supporting innovation. They disregard, however, a number of trends that potentially weaken their explanation. Some of these include:

- the increasingly narrow focus of dominant seed firm research, focusing on blockbuster traits for the largest markets, which undermines seed diversity and resilience (Schurman and Munro 2010; IPES-Food 2016)—MacDonald et al. cite increasing numbers of patents and Plant Variety Protection Certificates as evidence of increasing introductions of new seed varieties, but omit that these intellectual property protections are often broad claims on naturally occurring traits, and create barriers to innovation for small- and medium-scale seed companies (USDA 2023)

- the cultural reasons for the rapid adoption of expensive herbicide-tolerant seeds, such as avoiding straying too far from the practices of neighboring farms (Lockie 1997) or that weed free fields indicate “good farmers” (Burton 2004)

- loyalty programs that dominant firms allegedly operated with distributors in order to limit seed choices for farmers, as well as steer them toward more expensive options (Khan 2013)—the authors do mention how this tactic was allegedly applied in herbicide markets in order to keep prices high after their patents had expired

- manipulating choices available for farmers, such as reducing the number of seed varieties in their catalogs (particularly those that do not increase agrochemical sales—it is very difficult to find commodity seeds that are not treated with neonicotinoids (Hitaj et al. 2020), for example

- firms bragging about their power to set prices on earnings calls with investors, such as Corteva pointing out that their seed prices increases more than make up for higher material costs (Broughton and Francis 2021)

In the section focusing on meat processing, MacDonald et al. suggest that increasing plant size, driven by technological changes, largely accounts for the trend toward fewer and larger firms. They also suggest that these trends led to lower retail prices, at least initially (from the 1980s to about 2010). They fail to note, however, that the breakup of unions—including the use of illegal tactics by dominant firms—helped drive down wages to workers in meatpacking plants (Kwitny 1981). They neglect the significant costs to taxpayers resulting from these trends, including higher levels of pollution from more concentrated livestock operations and processing plants, and the burden on public services due to relying on immigrants for much of their labor force.

The authors do note recent trends toward higher retail meat prices and lower prices paid to livestock producers—described as an increasing price spread—particularly since 2015. They report allegations of collusion that may explain these trends, but also point toward the possibility that new plants built by livestock producer organizations may undermine this power of dominant firms.

In the section focusing on grocery retail, the authors again emphasize technological changes and scale economies as drivers of consolidation, but overlook a very significant factor—Walmart brazenly flouted the Robinson-Patman Act, which prohibits retailers from receiving discounts from suppliers based on purchasing higher volumes. As Walmart faced no enforcement consequences after entering the food industry in the 1990s, other large grocery retailers responded with mergers and acquisitions to achieve a similar scale. The ability of firms like Safeway and Albertsons to also demand price breaks disadvantaged smaller retailers, and catalyzed even more concentrated markets. Recent years have seen skyrocketing grocery costs, as well as record supermarket chain profits (Schweizer 2024).

Overall, MacDonald et al. do not probe deeply into their definitions of “efficiency.” They do not ask the questions suggested by Luke Herrine (2023):

- Efficient in what sense?

- Why should we care about that type of efficiency in this context?

We can add to this list:

- Efficient for whom?

- Innovative for whom?

- Who loses as a result of the ways that efficiency and innovation are typically defined, measured and subsidized?

These are the questions that need to be carefully considered before we conclude that industry concentration is largely positive.

References

Bain, C., Selfa, T., Dandachi, T., & Velardi, S. 2017. ‘Superweeds’ or ‘Survivors’? Framing the Problem of Glyphosate Resistant Weeds and Genetically Engineered Crops. Journal of Rural Studies, 51, 211-221.

Broughton, Kristen and Theo Francis. 2021. What Does Inflation Mean for American Businesses? For Some, Bigger Profits. Wall Street Journal. November 14.

Burton, Rob J.F. 2004. Seeing Through the ‘Good Farmer’s’ Eyes: Towards Developing an Understanding of the Social Symbolic Value of ‘Productivist’Behaviour. Sociologia Ruralis, 44(2), 195-215.

Gassmann, A. J., & Reisig, D. D. 2023. Management of Insect Pests With Bt Crops in the United States. Annual Review of Entomology, 68(1), 31-49.

Hitaj, C., Smith, D. J., Code, A., Wechsler, S., Esker, P. D., & Douglas, M. R. (2020). Sowing Uncertainty: What We Do and Don’t Know About the Planting of Pesticide-Treated Seed. Bioscience, 70(5), 390-403.

Herrine, Luke. 2023. What Do You Mean By Efficiency? An Opinionated Guide. Law & Political Economy Project. https://lpeproject.org/blog/who-cares-about-efficiency/

International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development: Global Summary for Decision Makers (IAASTD). 2008. http://wedocs.unep.org/handle/20.500.11822/7862

IPES-Food. 2016. From Uniformity to Diversity: A Paradigm Shift from Industrial Agriculture to Diversified Food Systems. International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems.

Khan, Lina. 2013. How Monsanto Outfoxed the Obama Administration. Salon. March 15.

Kwitny, Jonathan. 1981. Vicious Circles: The Mafia in the Marketplace. New York: Norton.

Lockie, Stewart. 1997. Chemical Risk and the Self-Calculating Farmer: Diffuse Chemical Use in Australian Broadacre Farming Systems. Current Sociology, 45(3), 81-97.

MacDonald, J.M., Dong, X., & Fuglie, K.O. 2023. Concentration and Competition in U.S. Agribusiness. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, EIB-256. https://doi.org/10.32747/2023.8054022.ers

Schurman, Rachel, and William A. Munro. 2010. Fighting for the Future of Food: Activists versus Agribusiness in the Struggle over Biotechnology. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Schweizer, Errol. 2024. Why a Price Gouging Ban Isn’t So Crazy After All. Forbes. September 4.

USDA, Agricultural Marketing Service. 2023. More and Better Choices for Farmers: Promoting Fair Competition and Innovation in Seeds and Other Agricultural Inputs. https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/SeedsReport.pdf